Fast food science is a shit sandwich

When it comes to technology and communication, faster is usually considered better. For example, test pilot Chuck Yeager showed “The Right Stuff” by being the first person to break the sound barrier. We celebrate computer chips becoming faster. In the age of the internet, many people view real-time interactive communication, such as on Twitter (more on this later!), as highly desirable. However, faster is not always better. Resisting the obvious and puerile joke, fast food is a clear example of faster not being best – It has its place but no one with any taste or class would argue that its the highest quality food, nor fit for occasions that are about more than convenience.

Yet, somehow when it comes to science, where one would think reflection and deep thought would be prized, a lot of the community seems to have moved toward the fast food model of thought. The ethos is that instant commenting and evaluation is somehow expediting science. It’s not, much like how the public is not better informed by virtue of the 24/7 news cycle. The science case is actually more insidious than sound-bite journalism as the scientists themselves are the ones who shape the story in their own ahistorical echo chambers.

I experienced this recently when a prominent journal reviewer, who we believe majorly lost the plot by confusing our theory paper as a methods paper, posted his negative review without our consent as a blog post (copycats followed) shortly after we received the journal rejection (see here and here for a discussion). This podcast has also been recommended to me on the issue.

Within moments, we were obliged to respond to defend ourselves. I spent years working on a project and somehow found myself completing and posting a public blog response within an hour, absurd. Fortunately, we got it right and our revision cements that case, which is how it usually goes when one spends years thinking about a project and critics don’t have that luxury.

What struck me was there was no actual scientific discourse on Twitter and there couldn’t be under these conditions for the type of work we do. It was chaotic. It was bizarre. We were tone policed by a social psychologist who didn’t seem to understand (skin in the game?) the situation but sure had to pick a side, all while ignoring the existence of the early-career-researcher (ECR) lead author. We had no time to digest people’s points and chart a response. Scientific debate on Twitter is akin to politicians trying to score points in an American-style Presidential debate. We scored our points for sure, but it’s not a game that we are interested in playing.

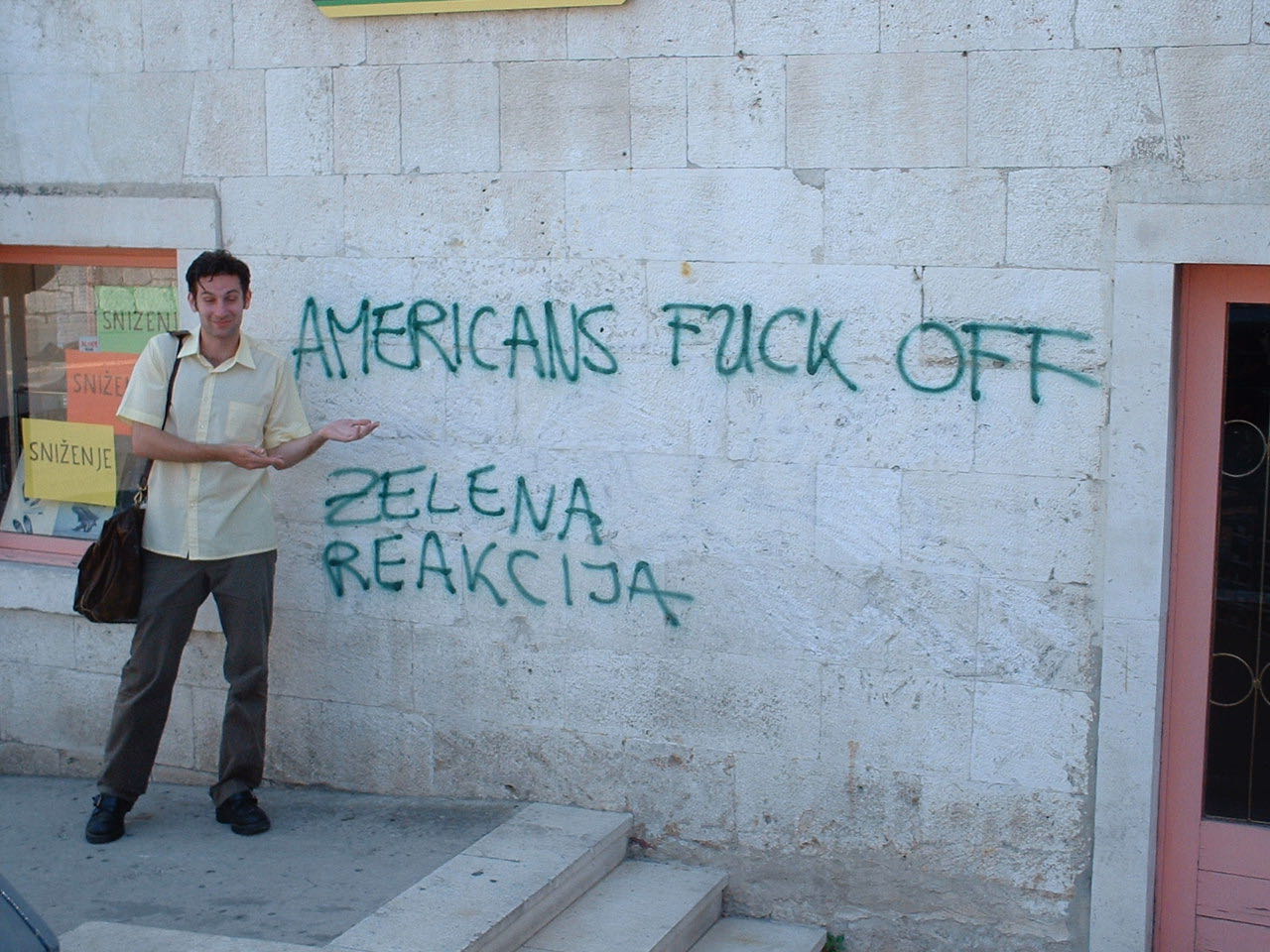

Social media can be cesspool open to abuse that stands in stark contrast to open review models (that all involve consent) at journals like eLife and computer science conferences like ICLR. In our view, science doesn’t truly progress from takedowns and hit-and-runs, but from people thinking deeply about what they are doing, often in light of the feedback from others when it can be fully and deeply processed. Open review should not be someone’s internet graffiti.

When we had time to dissect the attack blogs, which we did solely out of thoroughness as we did not find the points particularly relevant, we discovered that our main critic’s pet measure that supposedly is His gift to us wasn’t even really suited to our approach which relies on rank information. Still, others parrot the points of our critic’s musings absent thought, like that similarity and classifier functions are one-and-the-same because there exists examples of both that compute covariance information, which is the logical equivalent of concluding that two distinct species that both eat bugs under certain circumstances are one-and-the-same.

The point here is that, while it took us only moments to appreciate this critic missed our global point, it took weeks to appreciate that even the specifics were off the mark. Yet, people in moments were firing away opinions as facts (mostly by parroting one person’s views), lecturing us by tweet how science works, and telling us to sit back and enjoy it to make the most of it, which was all rather rapey and authoritarian. It would be bad enough if confined to Twitterverse, but this garbage thinking sticks and colours discourse, much like fake news does.

Twitter can exacerbate conflict through its dark triad of instant interaction and feedback, brief responses, and occasionally mob dynamics. Some seem to think they are owed a response because they questioned you or went to the trouble of writing a blog about you or (a blog about a blog) to the Kleene star. Here’s a hint, no one is obligated to respond to others’ hot takes. It is not a sign of strength and intellectual integrity to wade through the morass. Not everything dignifies a response, and even when something does it is not necessarily worth one’s time. Our preferred response is our revised preprint. Often, insta responding is a poor use of time and the people on the receiving end usually aren’t really processing what is said anyway. These rapid interactions favour narcissist bullshit merchants, who are exactly the folks you don’t want running a field. Dealing with them is effectively a Denial of Service (DoS) attack on actual thought, which is not expediting science. The experience can be consuming in the moment, but the half-life of thoughts on Twitter is brief.

Of course, media like Twitter can play positive roles in science, such as providing a means, albeit with a biased sample, to learn about recent work and people’s views and meet new people. I have learned a lot from people sharing information in direct messages (DMs) as well, and then there is the light-hearted banter. In contrast, real-time debate, especially when it’s a takedown on a particular person or paper, is unlikely to have valuable content.

It might be in science that you get to choose two from FAST, PROPERLY EXECUTED, INNOVATIVE. In my estimation, the last attribute is what is often lacking and what often goes under appreciated. I am advocating for giving scientists the opportunity to actually think. That’s why I got into this line of work. Sometimes it means sitting silently and thinking something through for a couple days and eventually getting it right after repeatedly doing so for months. In the open office plan of science, when people are expected to engage in instant debates that are formulated along the wrong dimensions, I just don’t see anything very deep or useful being produced. So, here’s for something better than cold fast food at the science banquet. Choose your dining partners carefully.