An Open Review of Niko Kriegeskorte

Imagine you think and work carefully on an ambitious paper for a few years, trying to answer fundamental questions the field has overlooked. Now, imagine after a very long wait you receive negative reviews that completely missed the main point. Instead, the reviews project a certain person’s pet concerns, goals, and interests onto your work, which are only tangentially related to your central questions. Worst yet, this person has acolytes whose capacity to miss the broader picture is only surpassed by their self-righteousness. That would be frustrating and potentially career-changing for some.

Now, let’s add to this scenario that this reviewer personally emails you moments after your rejection absent kind words (he got the memo that empathy is passé), but demands that you agree with his viewpoint and alerts you that he will post an open review of your work. This is inhuman.

But, open is good right? It can be, but it can also be incredibly self-serving. The review is of course open when Niko wants it to be and it serves him. Was the review posted before the editor made the reject decision? Of course not, because then we could respond and potentially affect the decision. Was it posted after we had time to publish elsewhere? Of course not. It was posted at the darkest time for my team when we are in our most vulnerable position when there’s little time to respond and we have more important things to worry about. Nevertheless, we are obliged to respond because Niko has poisoned the well for our project. “Open” here is not to serve the community or the authors but to provide a cheap blog and attention for Niko for the limited number of manuscripts that it serves Niko to review. The reinforcing power structure here should be apparent to anyone clued in.

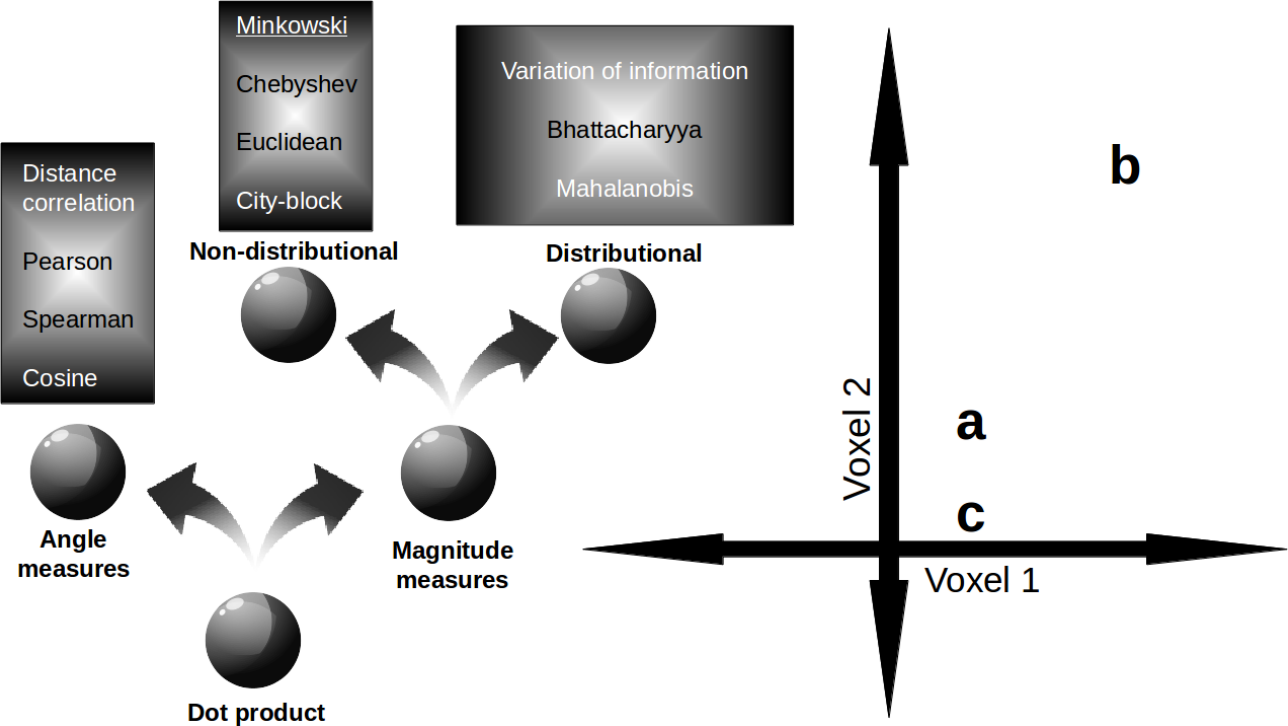

Our paper itself, which I encourage you to read and form your own opinion, is about the nature of neural similarity, namely what makes two brain states similar. The main questions are whether the brain’s preferred notion of similarity is different across regions and tasks. We find that the preferred similarity measures are common across regions but differ across tasks. This is cool. Of course, as we discuss, whatever measure is “best” (whatever that means and it does mean different things to different people) will depend on many issues, including data quality and quantity. We muse a bit on how these higher-level measures of similarity relate to underlying computations and representations. There’s been a ton of work in Psychology on what makes two stimuli similar, but in Neuroscience people largely default to a few options without any real evaluation. Thus, our work is very needed in the field and timely. We get traction on this neglected problem by using a decoding approach to approximate the information available in a brain state. We discuss how much this approximation should be trusted in light of our central questions, namely does the brain use the same similarity measure across regions and tasks.

Decidedly what we are not trying to do is determine which neural similarity measure has the best properties by some metric, such as split-half reliability, bias, whatever small methodological point is of interest to some. Of course, that is what primarily interests some, such as Niko, but these points are minor and largely inconsequential to our goals and conclusions. Niko provided a top-down reading of our work strictly through the lens of his interests that fails to engage with the main ideas of the paper. I leave it to the acolytes to review his papers, of which I am familiar. Again, please read our paper, rather than parrot Niko’s views.

As these sideshows entertain, fundamental questions about how to bridge from neurons to voxels to compact higher-level descriptions to computations remain unanswered. To make progress, the field needs leaders who are open to ideas and are broader thinkers. Of course, instead we have a system that entrenches and amplifies those in positions of power within the field. Rather than fall in line, my lab is trying to address these difficult and subtle questions. However, how can we make progress in the field when we are reviewed by people like Niko who doesn’t believe the brain has representations?

true, the brain does not need representations. it also doesn't need information or causality. it's a dynamical system after all. it's *us* who need causality, and information theory, and representational interpretations to understand the brain. https://t.co/8JatZUo1yt

— Kriegeskorte Lab (@KriegeskorteLab) August 12, 2018

While we can all laugh at the occasional pseudo profound cringe-inducing tweets by celebrities like Elon Musk, we should expect more from the leaders of our field. It’s intolerable for our scientific fate to be controlled by someone who is a Cartesian Dualist or is profoundly confused by levels of analysis. I am glad that Niko and others picked up on ideas from Roger Shepard and others from 1970 on second-order isomorphism and that they popularised others’ efforts to apply related ideas to the analysis of fMRI data. They have made a career out of correlating the upper diagonal of matrices and plodding through attendant concerns. Now it’s time to allow others to make progress and introduce new ideas into the literature.

Postscript: Lots of discussion on Twitter. To be clear, we are not against the eLife model of publishing reviews upon acceptance, nor are we against leaving comments on preprints, which can allow the authors to respond and perhaps make edits. We are against using the existence of a preprint as a pretext to write journal reviews which are really self-serving blog posts, especially when they are posted the moment one’s paper is rejected by the editor. This take on open reviewing is open to abuse and is not really open as the reviewer decides what, where, when and how. Furthermore, existing models of open review involve consent from all parties.

Also see the post by the first author too, here: Sebastian’s Thoughts on Open Review.