Backwards Compatible: The Strange Math Behind Word Order in AI

Probability 101: Does Order Matter in Sequences?

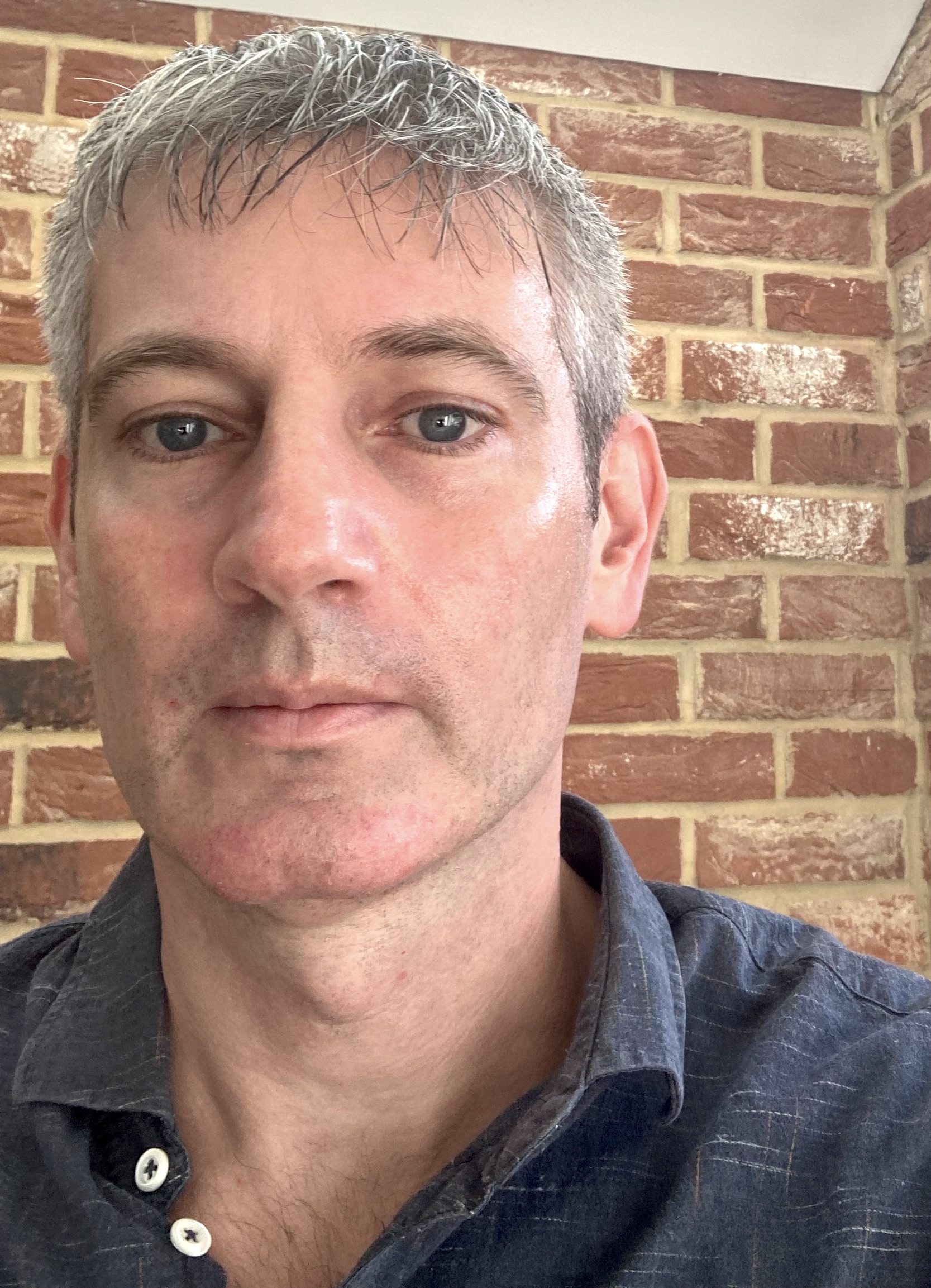

Ever tried reading a sentence backward? Or jumbling the words like a word salad? Take the sentence “The cat sat on the mat” as an example (Fig. 1). Imagine calculating how likely this exact sentence is to appear. Does it matter if you start with “The” and work forward, or begin with “mat” and go backward, or even shuffle the words randomly? Your gut might say, “Yeah, scrambling it feels way harder!” But here’s the wild part: math says the probability of the whole sentence stays the same, no matter the order you process it in. Let’s unpack why.

We’re talking about the joint probability of the full sequence, P(The, cat, sat, on, the, mat), which measures how likely it is for all six words to appear together in that order. You can break this down into steps, and the order of those steps shouldn’t change the final answer. Here’s how it looks:

Forward order: Start with “The” then find the chance of “cat” given “The” then “sat” given “The cat” all the way to “mat” given “The cat sat on the.” That’s: P(The) × P(cat | The) × P(sat | The, cat) × P(on | The, cat, sat) × P(the | The, cat, sat, on) × P(mat | The, cat, sat, on, the)

Backward order: Flip it! Start with “mat” then the chance of “the” given “mat” then “on” given “mat the” up to “The” given all the rest. That’s: P(mat) × P(the | mat) × P(on | mat, the) × P(sat | mat, the, on) × P(cat | mat, the, on, sat) × P(The | mat, the, on, sat, cat)

Shuffled order: Mix it up, like starting with “sat” then “The” then “mat,” and so on. One mix could be: P(sat) × P(The | sat) × P(mat | sat, The) × P(on | sat, The, mat) × P(the | sat, The, mat, on) × P(cat | sat, The, mat, on, the)

The magic? All these paths—forward, backward, or shuffled—land at the same joint probability, P(The, cat, sat, on, the, mat). This is thanks to the chain rule of probability, which keeps the math consistent. A measure called perplexity, which shows how certain a model is about the sequence, should also be identical across these orderings, given by: \(\exp \left(-\frac{1}{6} \ln P(\text{The, cat, sat, on, the, mat})\right).\) So, in theory, whether you read the sentence forward, backward, or as a jumbled mess, its predictability stays the same. We prove this equivalence mathematically and provide the full derivations in our paper here.

Do LLMs Produce Perplexities Consistent with Theory?

Large language models (LLMs), like the GPT-2 models we studied (with 124M, 355M, and 774M parameters), learn by predicting the next word in a sentence, a process called autoregressive training. They break down a sentence into tokens (words or parts of words) and estimate conditional probabilities—like the chance of “sat” following “The cat”. This mirrors our probability example, suggesting that LLMs should, in theory, produce the same perplexity for a sequence whether it’s processed forward, backward, or shuffled. But do they?

We trained GPT-2 models on a massive dataset of neuroscience papers (1.3 billion tokens, spanning 20 years) in three ways: forward (normal reading order), backward (reversed token order), and permuted (randomly shuffled tokens within each sequence). If the theory holds, all models should have the same perplexities for the same text. But what happens in practice?

What We Found: Theory Meets Reality

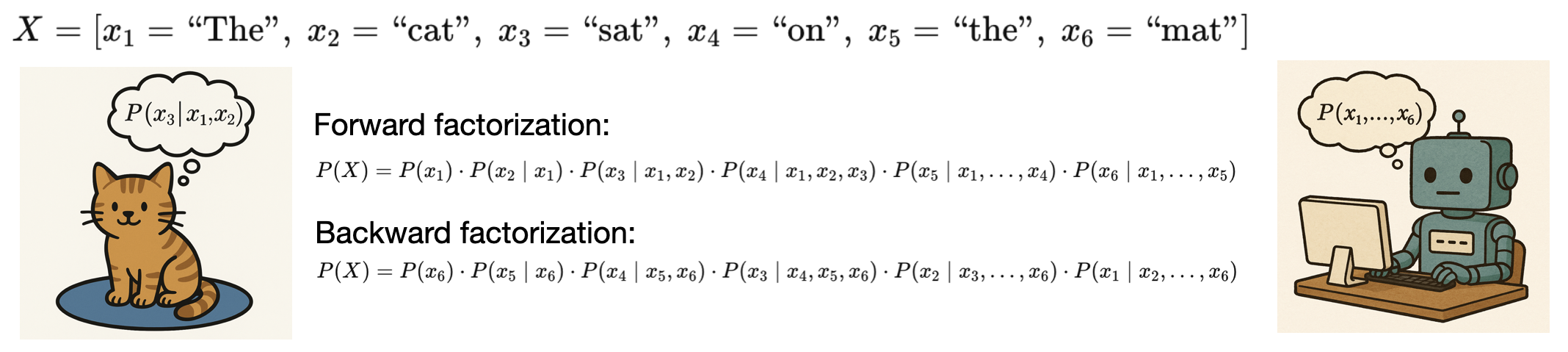

Surprisingly, the models didn’t perfectly align with the theory. Forward and backward models had similar perplexities, but forward models consistently performed slightly better, meaning they were less uncertain about predicting sequences. Models trained on permuted (shuffled) text, however, showed much higher perplexities, deviating significantly from both forward and backward models (Fig. 2). This suggests that shuffling tokens makes prediction much harder for the model.

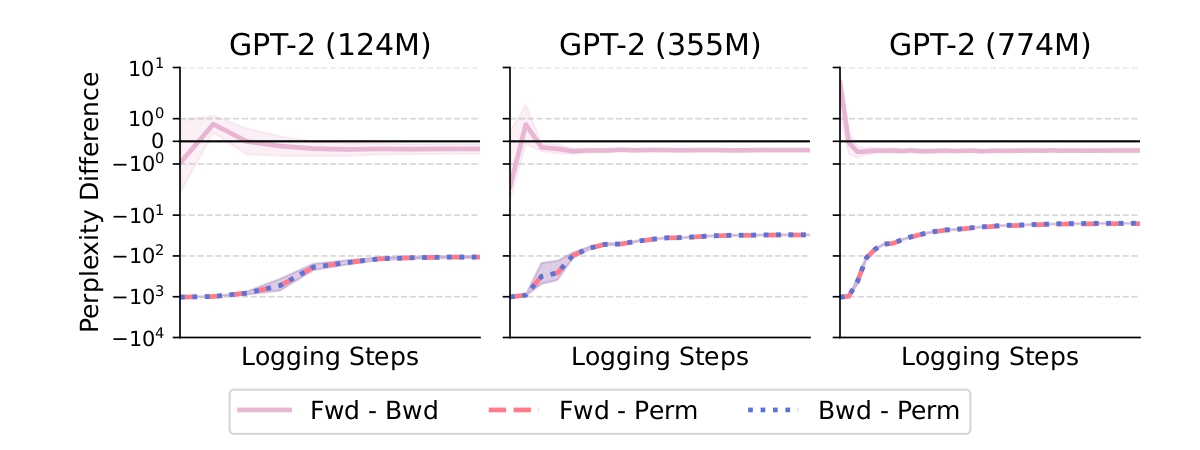

We dug deeper to understand why. The culprit? Attention biases in how these models process text. LLMs use a mechanism called self-attention to weigh the importance of different tokens in a sequence. We found that forward and backward models tend to focus heavily on nearby tokens and those at the start or end of a sequence, irrespective of the meaning of those tokens. Permuted models, however, developed very different attention patterns (Fig. 3). Biases toward specific token positions can affect how a sequence is processed when factorized in different orders, with these differences cascading through the model and leading to variations in perplexity.

Some recent studies have also observed that language models perform differently when trained on forward versus backward text. However, their findings or explanations are flawed or incomplete due to experimental setups that violate theoretical principles. We provide a detailed discussion in our preprint.

How do forward and backward models perform on benchmarks?

We’ve shown that our models differ in their perplexity and attention patterns. But how different are they when put to a real test? To find out, we evaluated them on BrainBench, a benchmark that challenges models and human experts to predict the outcomes of neuroscience experiments (see the original Nature Human Behavior paper here). BrainBench presents pairs of study abstracts—one real, one altered to change the results but still sound plausible—and asks which is correct. This task tests model’s ability to spot patterns in complex scientific texts, making it a perfect fit for our models trained on neuroscience literature.

The results? Our forward and backward models performed remarkably similarly, showing that their differences in training order don’t significantly impact their ability to predict neuroscience outcomes. Importantly, both models, especially at larger sizes (like our 774M-parameter GPT-2), rivaled and often surpassed human experts.

This finding speaks to a bigger debate: are large language models (LLMs) good models of human language learning? Humans learn language in a forward, meaningful order, but our models learned effectively across forward, backward, and even shuffled sequences to some extent. This suggests LLMs are perhaps not just mimicking human language but are general learning machines, capable of capturing predictive patterns in any data, even when it doesn’t follow human-like structure. Their success on BrainBench, especially for backward models, mirrors how LLMs excel in non-human-language domains—like scientific data or code—where patterns don’t always resemble natural language. This versatility challenges the idea that LLMs are limited to human-like learning.

What This Means for LLMs?

Our findings reveal a gap between theory and practice. Theoretically, the order of tokens shouldn’t affect a model’s perplexity, but in reality, LLMs are sensitive to how sequences are presented. These deviations could signal deeper issues, like untrustworthy outputs or even hallucinations—when models generate convincing but incorrect information. Understanding these biases helps us build more reliable models. Here, we’ve shown that training sibling models on the same data provides a way to evaluate how internally consistent LLMs are in terms of their inferred probabilities.

For full details and extended results, check out our preprint, code, and model weights.