A neuroscience-inspired approach to transfer learning

Inspired by the brain, we find a goal-directed attention approach to feature reuse bests a commonly used machine learning strategy (Luo et al., 2020). In particular, attentional modulation of mid-level features in deep convolutional neural networks is more effective than retraining the last layer to transfer to a new task.

Neuroscience and machine learning have been enjoying a virtuous cycle in which advances in one field spurs advances in the other. For example, deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) were motivated by the organisation of the visual cortex. In this blog, we highlight another success for neuroscience-inspired approaches, namely using goal-directed attention to repurpose an existing network for a new task.

Goal-directed attention in humans

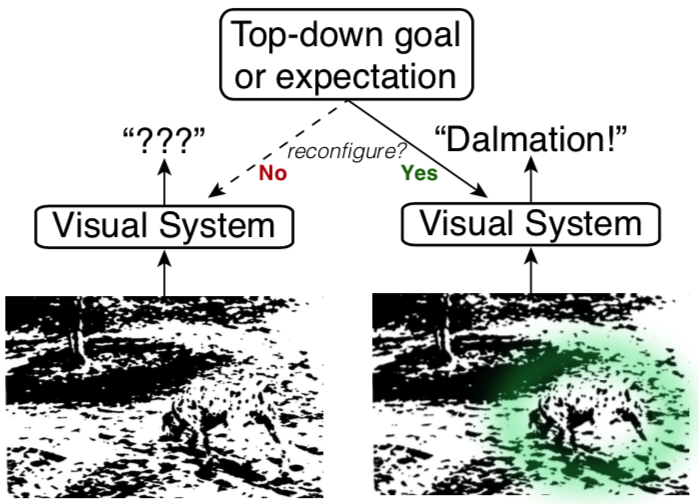

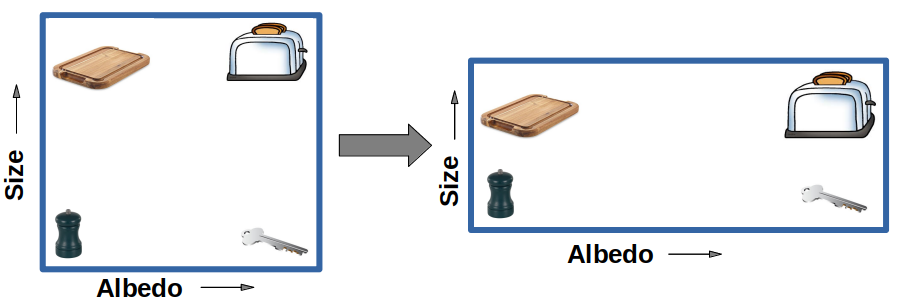

When searching for one’s car keys, a sensible strategy is to prioritise small and metallic objects. Focusing on goal-directed features at the expense of irrelevant features can increase one’s chances of finding the target item. Instead of retraining one’s brain for this particular recognition task, people use goal-directed attention to modulate activity in their visual system.

Conventional transfer learning in machine learning

In contrast, one popular method for transfer learning in machine learning is to remove the final layer of the DCNN and retrain it for the new task. Like the attentional approach, most aspects of the original network are preserved. For example, all the useful features previously learned could be reused for a task that prioritises finding one’s keys. To provide another example, a DCNN model pre-trained on ImageNet could be fine-tuned into a cats-vs-dogs detector using very little data.

An alternative approach: goal directed attention

Goal-directed attention and transfer learning approaches reuse existing features, but there is a critical difference. In the brain, goal-directed attention primarily operates at mid- to late-stages of the ventral visual stream. Our networks with goal-directed attention operate similarly. In contrast, transfer learning adjusts features at the very end of a DCNN. How does a neuroscience-inspired approach compare to the standard machine learning approach?

Here, we describe a study in which we incorporate goal-directed attention into the mid-level of a DCNN and use it as an alternative to the transfer learning approach. Results from three object recognition tasks favour the neuroscience-inspired approach both in terms of performance and ability to scale.

Incorporating goal-directed attention in DCNN

In cognitive neuroscience, goal-directed attention is a mechanism that emphasises or de-emphasises features based on their task relevance. This is often formalised as the stretching and contracting of psychological feature dimensions.

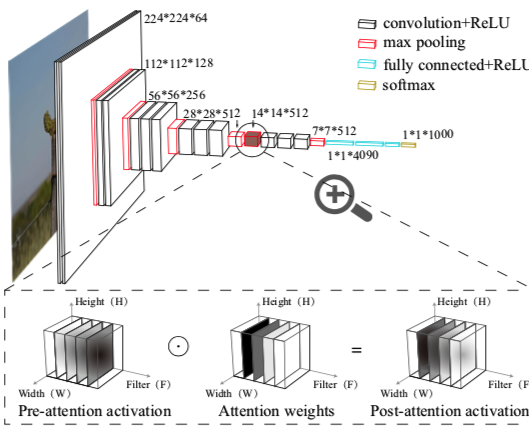

To incorporate this principle into DCNN models, we introduce a goal-directed attention layer at the mid-level of a pre-trained DCNN that can direct its focus on a set of features based on their goal relevance.

Attention beats convention

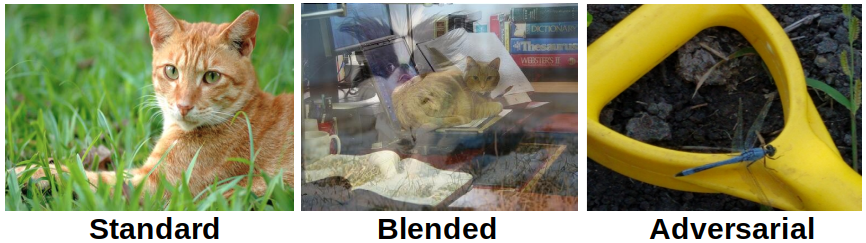

Models trained on ImageNet using either approach are tested on three object recognition tasks involving standard ImageNet images, blended images and natural adversarial images. Natural adversarial images exploit vulnerabilities in DCNNs such as colour and texture biases (Hendrycks et al., 2019).

All three tests follow the same procedure involving both target and non-target images. For example, when testing a model dedicated to detecting Chihuahuas, an equal number of Chihuahua and non-Chihuahua images are used to tune the network. For each model, we assess performance using signal detection theory.

We found that the goal-directed attention approach generally outperformed (i.e., higher $d^\prime$) the widely used transfer learning approach in all three tasks.

One explanation is that even though the attention layer had fewer tunable parameters ($512$ vs. $4,096,000$ parameters) than the retraining approach, the cascading effects through subsequent network layers provided the needed flexibility to match the task goal. The results suggest that this neuroscience-inspired approach can enable the model to more effectively adapt to new tasks at a relatively low cost. Additionally, since each attention weight has a unique correspondence to the entire feature map from the preceding layer, this goal-directed mechanism can potentially be more interpretable than the fully connected weights.