Giving LLMs too much RoPE: A limit on Sutton’s Bitter Lesson

Introduction

Sutton’s Bitter Lesson (Sutton, 2019) argues that machine learning breakthroughs, like AlphaGo, BERT, and large-scale vision models, rely on general, computation-driven methods that prioritize learning from data over human-crafted priors. Large language models (LLMs) based on transformer architectures exemplify this trend, scaling effectively with data and compute. Yet, positional embeddings—a key transformer component—seem to challenge this philosophy. Most embedding schemes are fixed, not learned, and embed a human-designed prior that words closer in a sentence are more relevant than those farther apart. This blog explores this machine learning practice that appears to defy the Bitter Lesson. We also analyze patterns in learned absolute positional embeddings, which partially align with fixed, human-designed schemes but show intriguing variations, highlighting the complexity of positional encodings in LLMs and the need for further research.

Why Transformers Need Positional Embeddings

Transformers process tokens in parallel using permutation-invariant attention mechanisms, lacking inherent sequence awareness. Without positional information, they treat “The cat sat on the mat” and “Mat the on sat cat the” identically, despite order being critical for meaning in language. While LLMs may learn word order differently from humans, they require consistent order encoding to function (see our recent blog for more). Positional embeddings provide this order, using either fixed or learned methods. Human intuition suggests nearby words are more relevant than distant ones, implying a decay in influence over distance—a prior often baked into positional encoding designs. However, Chen et al., 2024 argue this assumption may be outdated for modern LLMs.

A Brief History of Positional Embeddings

Early Positional Embeddings: Baking in Long-Term Decay

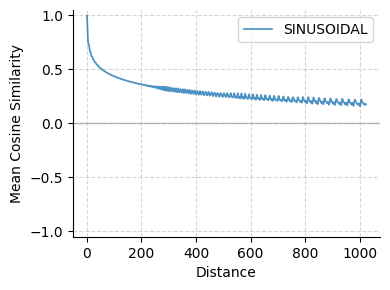

The original Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) used sinusoidal positional embeddings, applying deterministic sinusoidal functions to encode positions. These embeddings exhibit long-term decay, where similarity between embeddings decreases with token distance, aligning with the intuition that distant tokens are less relevant (Fig. 1).

Absolute Learnable Embeddings: Data-Driven but Limited

Absolute learnable positional embeddings, used in models like BERT, GPT-1, GPT-2, Galactica, and OPT, align with Sutton’s Bitter Lesson by assigning trainable vectors to each position, allowing the model to learn positional relationships from data. This data-driven approach avoids human priors, theoretically enabling optimal patterns to emerge during training. However, these embeddings are limited by a fixed maximum sequence length, hindering generalization to longer contexts.

Current Generation Embeddings: Back to Human Priors

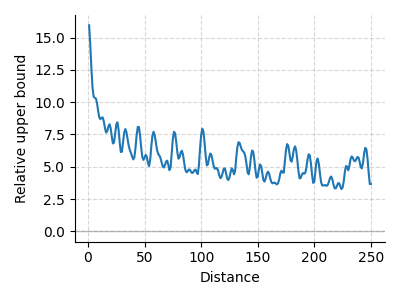

State-of-the-art models like LLaMA, Qwen, and DeepSeek use Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) (Su et al., 2021). RoPE applies fixed, relative rotations in attention, reintroducing a human prior of long-term decay (Fig. 2) while enabling length extrapolation—a key advantage for modern LLMs. This shift seems to step back from the data-driven ideal, suggesting that learning from data may not always be optimal, especially given practical constraints like context length.

Absolute Positional Embeddings: Revisited

Why did the field shift from human-designed fixed positional embeddings to a data-driven approach consistent with Sutton’s Bitter Lesson, only to return to fixed schemes? To explore this, we investigate learnable absolute positional embeddings, uncovering patterns that warrant further study.

Across various model sizes, architectures, and training datasets, these embeddings partially converge on the long-term decay seen in fixed embeddings. Surprisingly, they also show periodic oscillations, a byproduct in fixed embeddings designed for decay but lacking clear theoretical justification. Their presence in learnable embeddings is puzzling, varying with model capacity, architecture, and training data. Are these oscillations beneficial or artifacts? Their variability underscores the need for further research to clarify their role and optimize positional encodings in LLMs.

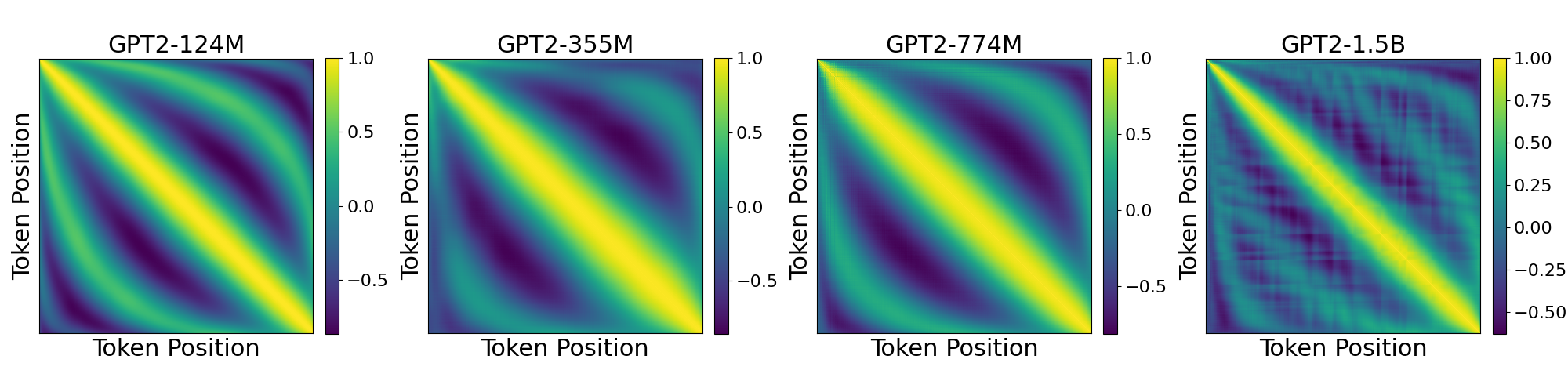

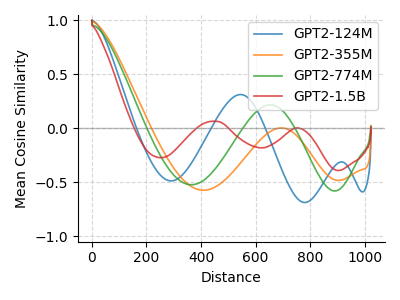

GPT-2: A Periodic Surprise

We analyzed cosine similarities of positional embeddings in pretrained GPT-2 models (Fig. 3). The top panel shows pairwise similarities between token positions, and the bottom averages similarities by distance. A smooth, periodic pattern emerges, noted in research and blogs, but without clear explanation. One might assume models capture hierarchical structure in training data, but this doesn’t hold: the pattern persists across diverse datasets without aligned peaks. Why does a data-driven approach produce such structured patterns?

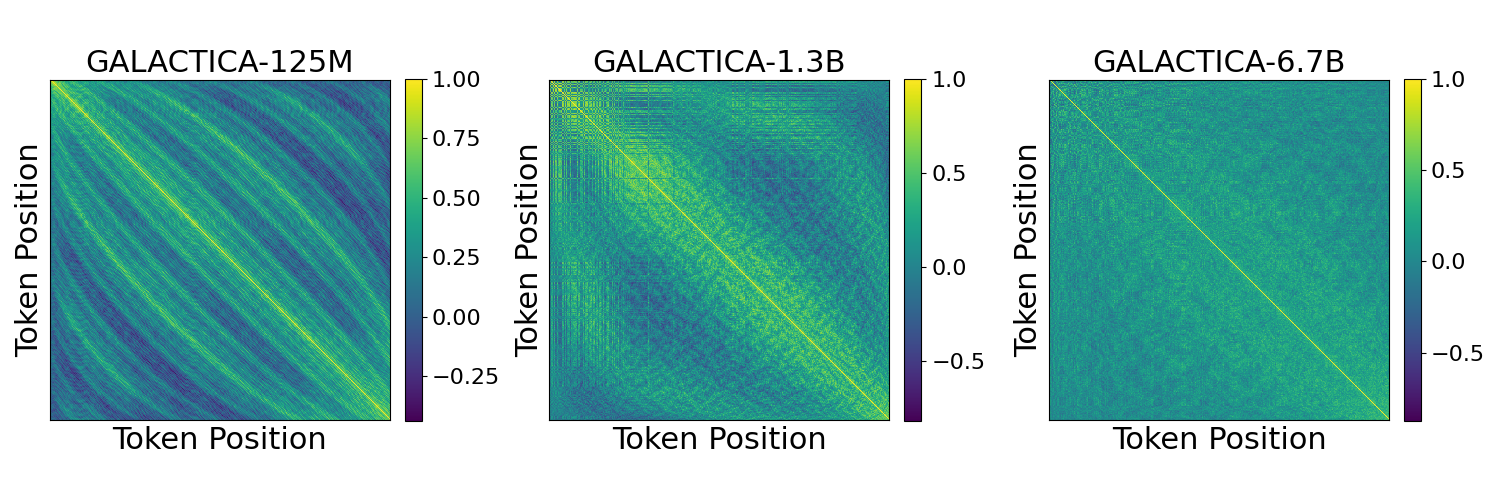

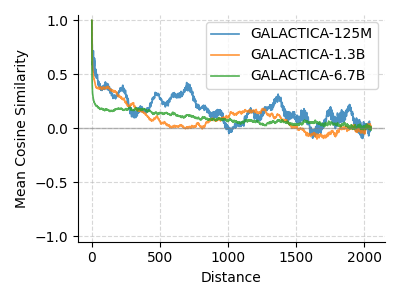

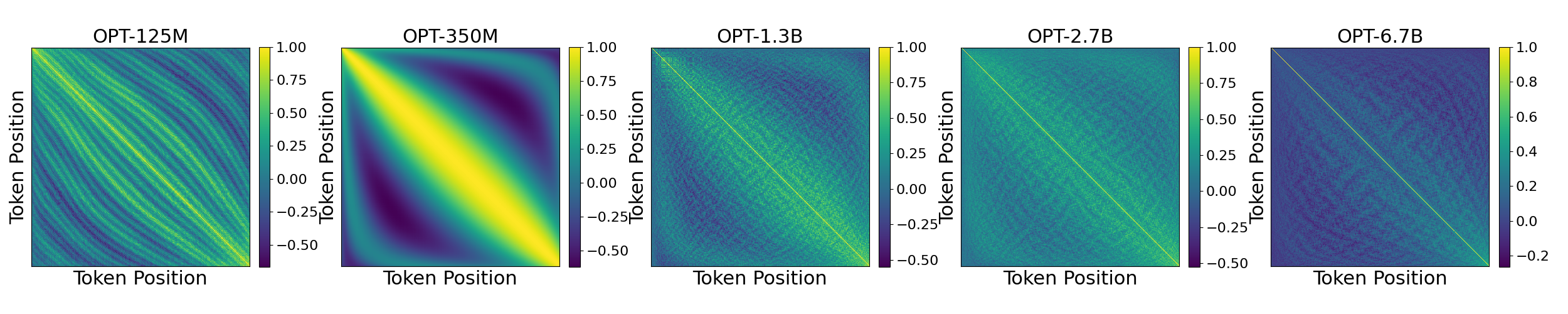

Varying Patterns Across Models

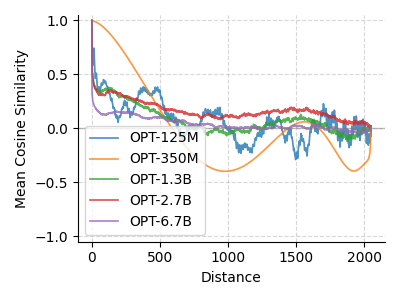

We examined Galactica (125M, 1.3B, 6.7B), trained on academic papers, and OPT (125M, 350M, 1.3B, 2.7B, 6.7B), trained on general text. Galactica’s smaller models show periodicity, but the 6.7B model trends toward a simpler similarity decrease (Fig. 4). OPT models vary: the 350M model mirrors GPT-2’s periodicity, while the 125M and larger models diverge, losing periodic structure (Fig. 5).

Training Data’s Role

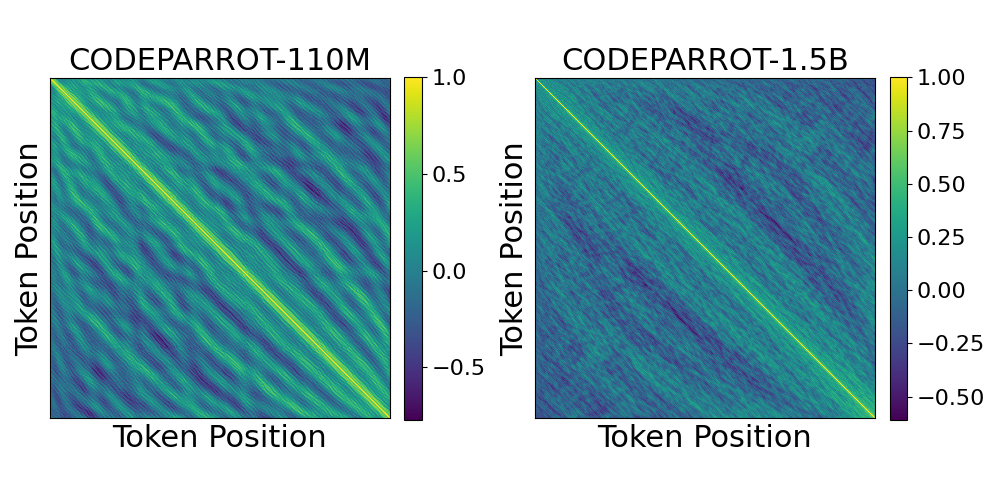

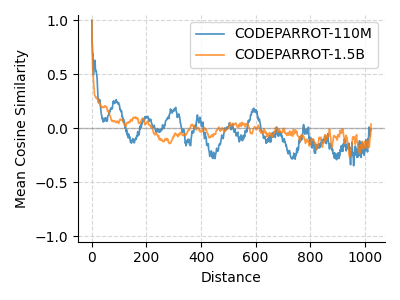

We analyzed CodeParrot (110M, 1.5B), GPT-2-based models trained on Python code. The 110M model shows periodicity distinct from GPT-2’s 124M, and the 1.5B model diverges further, unique from both smaller CodeParrot and same-sized GPT-2 models (Fig. 6). This suggests training data shapes these patterns.

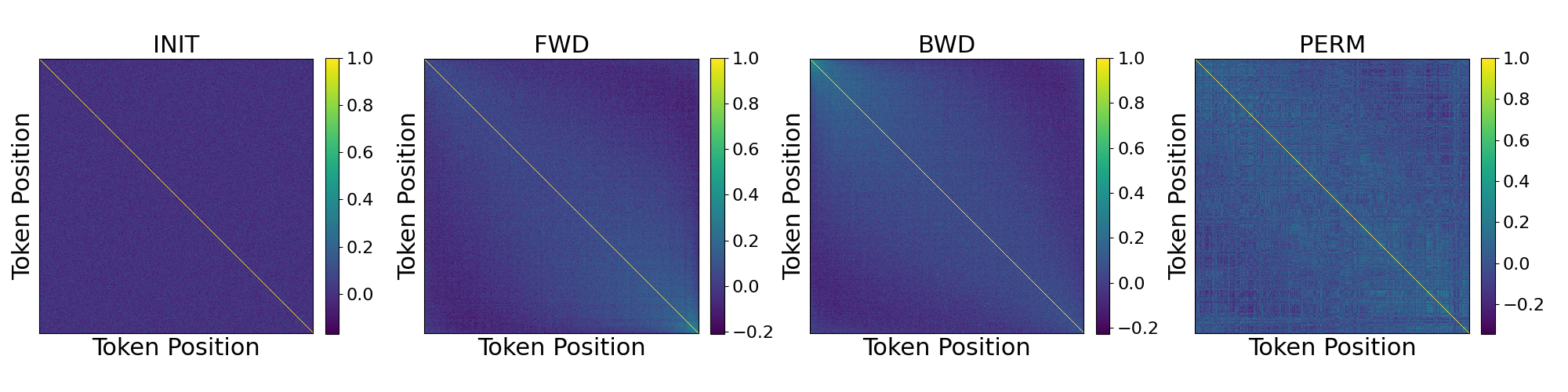

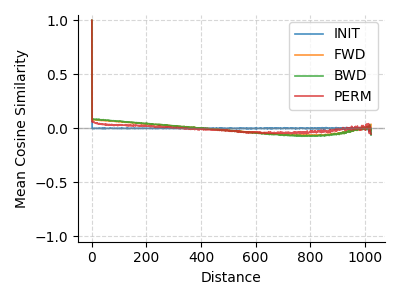

We also studied GPT-2 124M variants trained on neuroscience articles in forward (FWD), backward (BWD), and permuted (PERM) orders, detailed in a blog and paper. These show a weak similarity decrease up to 450 tokens, dipping negative before returning to zero, distinct from other models and a random baseline (INIT) (Fig. 7).

A Frontier to Sutton’s Bitter Lesson

The shift from absolute learnable positional embeddings to RoPE in modern LLMs highlights a trade-off between Sutton’s data-driven ideal and practical scalability. Learnable embeddings align with the Bitter Lesson but are limited by fixed context lengths, while RoPE’s fixed decay enables length extrapolation at the cost of reintroducing human priors. Both fixed (e.g., sinusoidal) and learnable embeddings exhibit periodic oscillations, but in fixed embeddings, these are a byproduct, with decay as the intended design. Their purpose remains unclear.

Intriguingly, learnable embeddings’ oscillations suggest partial convergence with fixed methods, but models like GPT-2 (all sizes) and OPT-350M show exaggerated oscillations, raising concerns about potential degenerative solutions or training artifacts. In contrast, models like Galactica-6.7B and larger OPT (and the smallest OPT) variants display more desirable decay with oscillations that adapt to training data and model scale. This flexibility, absent in RoPE’s rigid structure, may better capture nuanced patterns but risks instability. Are these oscillations beneficial or artifacts? They are unlikely to capture hierarchical structure in text, as peaks and troughs do not align across model sizes and architectures, but the periodicity may help distinguish positions, especially at greater distances.